Chuckie’s parents had spent over half their lives in the deep south of Mississippi before sometime in 1929 picking up and moving with their three adolescent children up north to Western Pennsylvania. What had changed for the Wilson family?

There are just three known images of Chuckie’s immediate family in the late 1920s that survive. The first is a group photo in an earlier post of a happy family picnic, a celebration of some sort outside the family farmhouse. Or, more likely perhaps, a going away party for the Wilson family moving up North for opportunity and a new life. The two other images have always haunted me because they are so strikingly different.

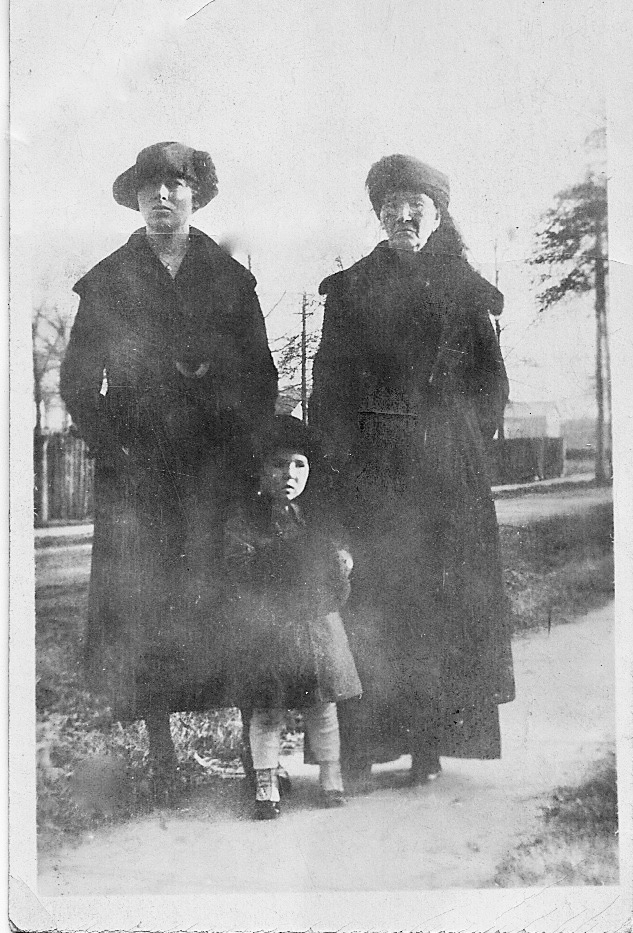

Darkness and cold – faces of grief

The first image is Chuckie’s mother Evie standing next to her mother Mary (Chuckie’s grandmother) with his little sister (also Mary, named after grandmother, of course) with her little hands in a muff. All three are dressed in black. No one is touching. From the background we can see it’s late Fall or early winter. What had happened that day to bring such great sadness to the Wilson family? They were not wealthy farmers or landowners, as far as we know, so the stock market crash of October 1929 was unlikely the reason. The Great Depression was yet to come.

Curiosity gave me some clues. A bit of research filled in some gaps. And soon it was not hard to arrive at an explanation. The unmistakable picture of a mother‘s grief for the loss of a child, and a sister for the loss of a sibling.

Chuckie’s mother had a very big family. She often told me about her “ten brothers and sisters” and how close they were. I went back to revisit our family tree. It was there I found an explanation for this photo. Two of her adult sisters, the daughters of Mary, died just one month apart. First Lucy in Dec 1928 and then Minnie in January 1929. Almost certainly this photo was taken on the day of one of those funerals.

That year, Chuckie’s grandmother Mary also left her home and moved up North at the age of 74 and lived with Chuckie’s family. She never returned again until years later when her body was returned to Mississippi in 1938 after her death.

Lightness and air – faces of warmth

The second image is taken obviously some months later that year and it is summer – up North. Chuckie’s mother and sister are bathed in sunlight washing over them from behind them on a breezy porch. They’re wearing cool, bright clothing and showing warmth, love and affection.

Chuckie’s father was, by all accounts, a good mechanic and legendary handyman who could fix anything. Up North, he quickly got a job applying those talents in a bread bakery operation that supplied fresh bread to the grocery stores feeding the families in the region’s large and growing population of factory workers, steel workers and manufacturing plant workers.

Around the time of the family move up north to Western Pennsylvania in 1929.

Evie would years later herself experience what is captured on her mothers face so vividly, starkly on that cold dark day in 1929 – the enormous, unbearable grief felt by a parent who loses a child. In 1944, her son Chuckie would pay the ultimate price for freedom in a country far, far away from her, his father, his siblings and Wilson family roots in the deep American south.