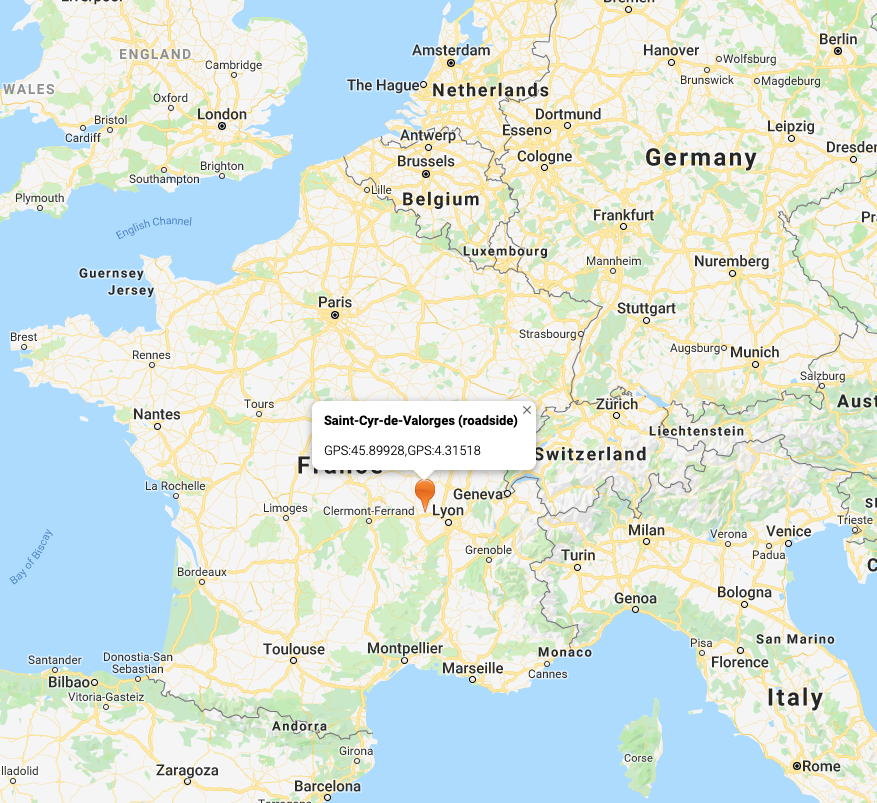

It was now morning daylight. Sometime in the morning hours, members of the French resistance army removed the remains of Chuckie and his four fellow comrades from the wreckage of the plane in a field near Saint-Cyr-de-Valorges, France and buried them in an unmarked temporary grave. They also worked very hard to quickly retrieve all the container canisters and packages of supplies strewn about and to hide them.

The Nazi’s would soon arrive at the crash site to retrieve any intelligence they could find.

Quickly burying the dead while under threat of the imminent danger of the arrival of the Nazi’s was a humane act of enormous compassion and respect by the French people. They protected Chuckie and the other fallen from any potential further desecration by the Nazi’s. It also allowed for Chuckie’s body to be identified and, at a later point, safely moved to a temporary cemetery and his subsequent permanent interment in December 1948 at his final resting place at Rhone American Cemetery in Draguignon, France.

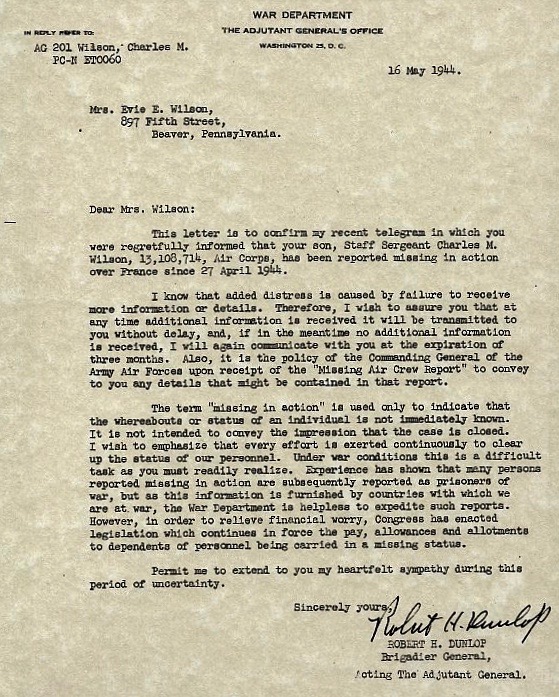

Chuckie’s parents were never given many facts about how he died because on his “S E C R E T” Carpetbagger mission. They did have the comfort of knowing that their their son’s body was always treated with the dignity and respect he deserved for paying the ultimate sacrifice for Freedom.

Chuckie’s family never saw these photos of his crashed plane.

Today, they are easily findable by anyone on the internet.

This is the underside of the bombay compartment in the center of the aircraft and the tail section section.

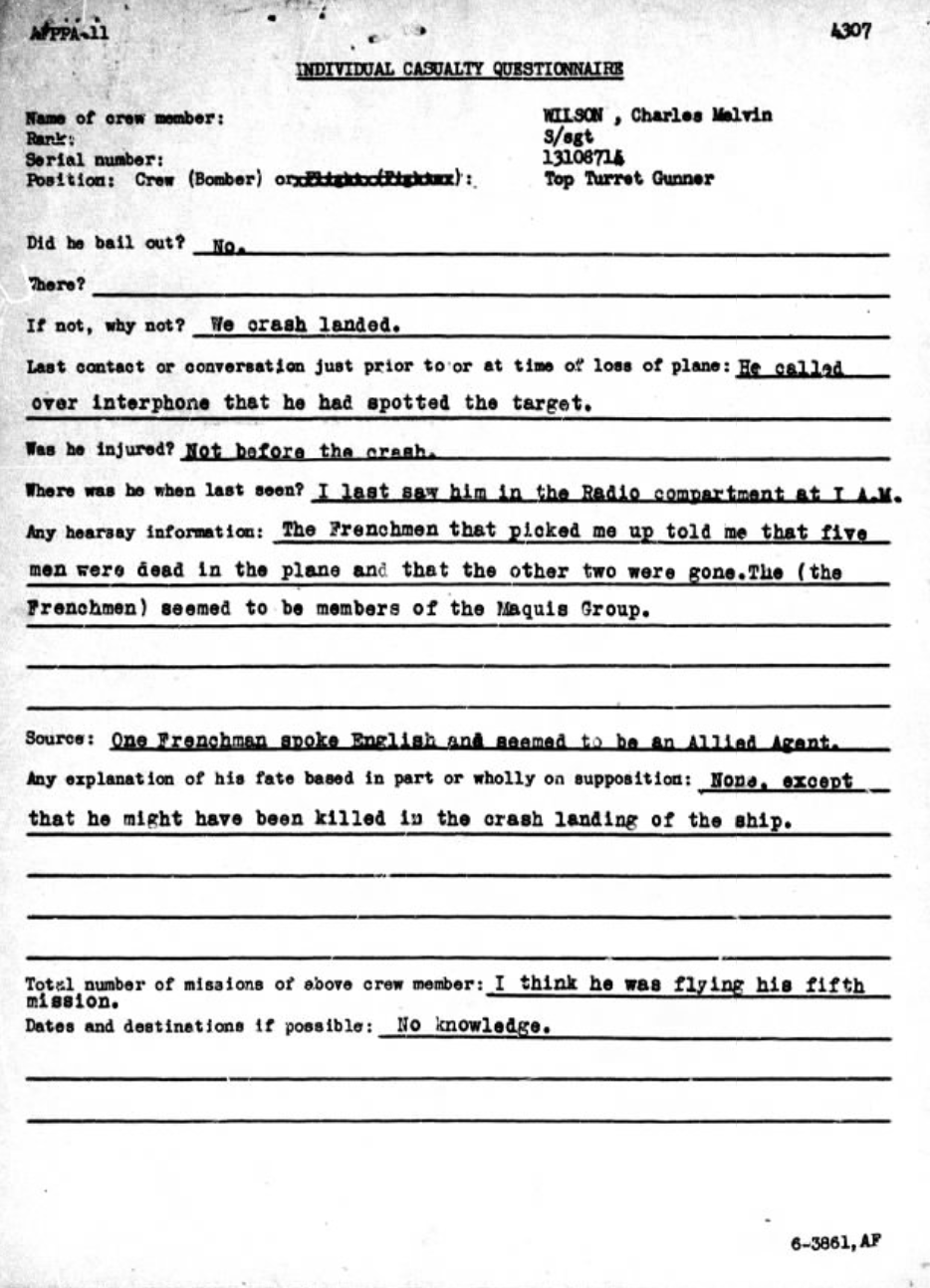

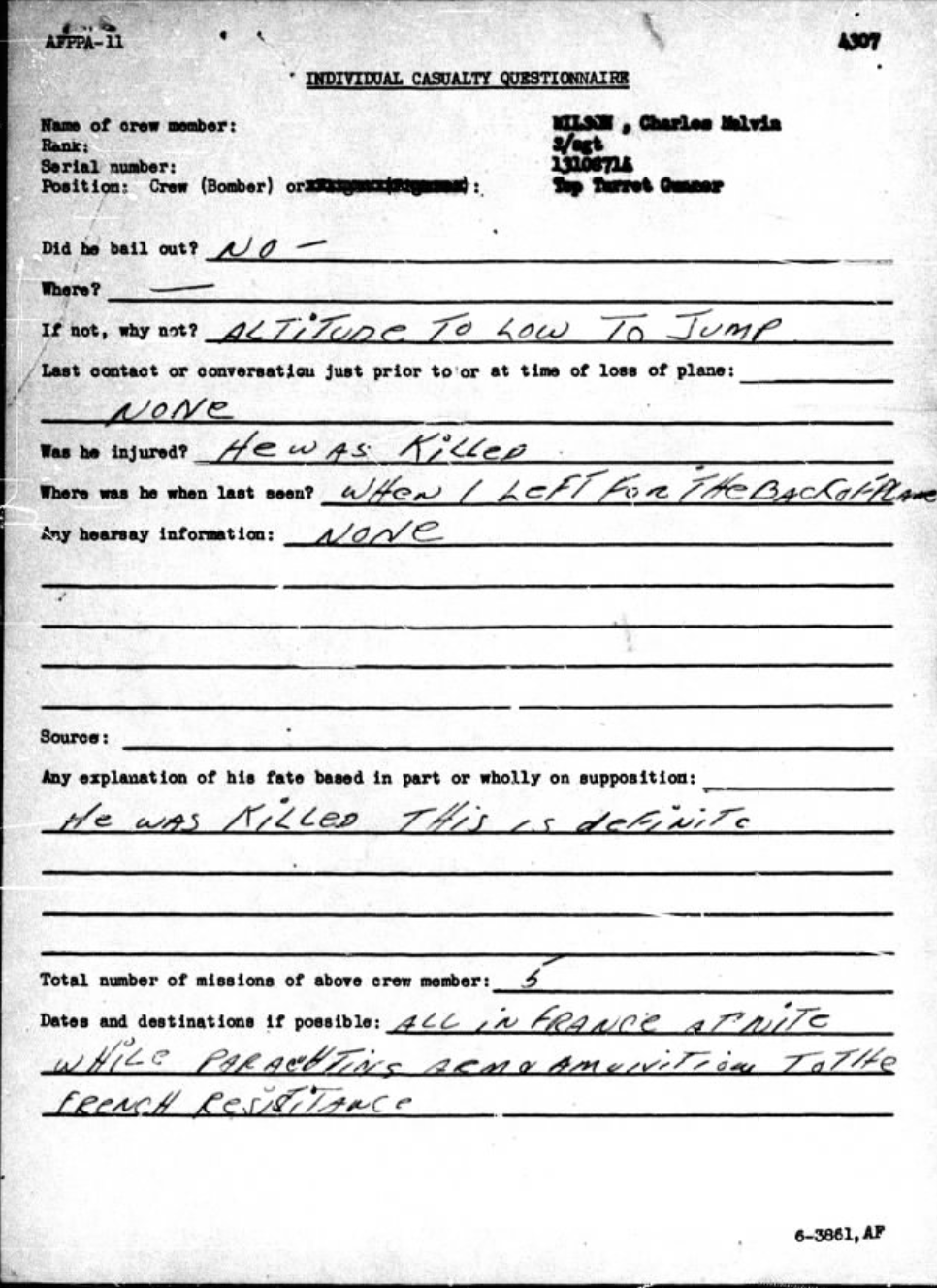

Killed In Action – 28 April 1944

Lieut. George W Ambrose, Pilot; of Springdale, PA

Lieut. Robert H Redhair , Co-Pilot; of Bartlesville, OK

S Sgt. Charles M Wilson, Engineer; of Beaver, PA

Lieut. Arthur B Pope, Navigator; of Fulton, GA

Lieut. Peter Roccia, Bombardier; of Washington, D.C.

“It was the next day that they (the French) realized that two more Americans survived (in addition to Mooney). They found the chutes, 1st one and then another, which they immediately buried.“

Survivors of the crash included:

Sgt. James J Heddleson, Radio Operator; of Louisville, OH

Sgt. George W Henderson, Tail Gunner; of Santa Monica, CA

Sgt. James C Mooney, Dispatcher; of Englewood, NJ – He volunteered for this mission (his first) – the rest of the crew only met him shortly before take-off, as regular crew member Sgt. W. Bollinger had reported off sick that day.

“We assumed everyone was killed except Sgt. Mooney.

His condition was such, I found out later, that the man whose house he was taken to, had to turn him over to the Germans. He told me personally how sorry he was for having to do this. But I tried to assure him that in Sgt Mooney’s case (broken back) he probably saved his life as I heard the Germans took him to a hospital.“

Heddelson and Henderson were now on the move to evade the enemy, as trained

“We moved only at night as we traveled quite a way for the shape we were in. The French started to look for us they said in every direction possible. We skirted villages and main roads, avoiding everyone we saw, especially the Germans. Having no idea where we were, we headed South.”

Edited from transcribed copy of letter by crash survivor James Heddelson in the archives at the Air Force Academy June – 1998

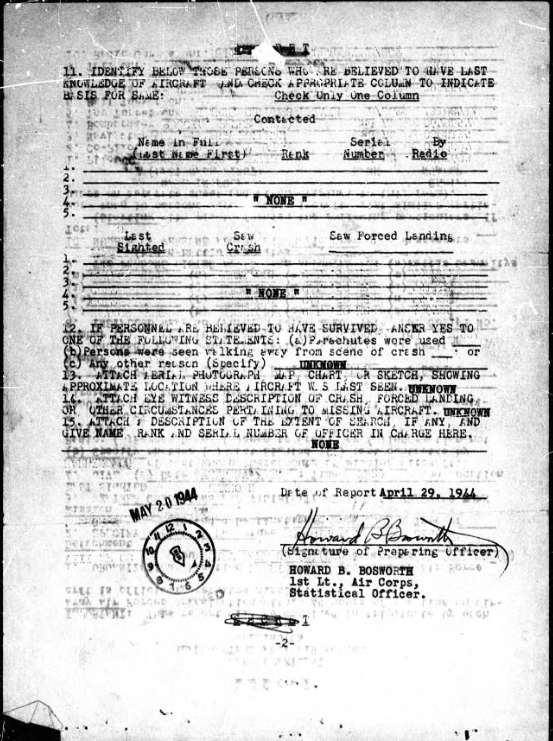

A French secret agent on the ground that day also took the piece of the plane with the serial number.

It would soon be returned back to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) headquarters at Baker Street in London as part of his field report to the Allied Forces command that the plane had crashed and USAAF men had died.