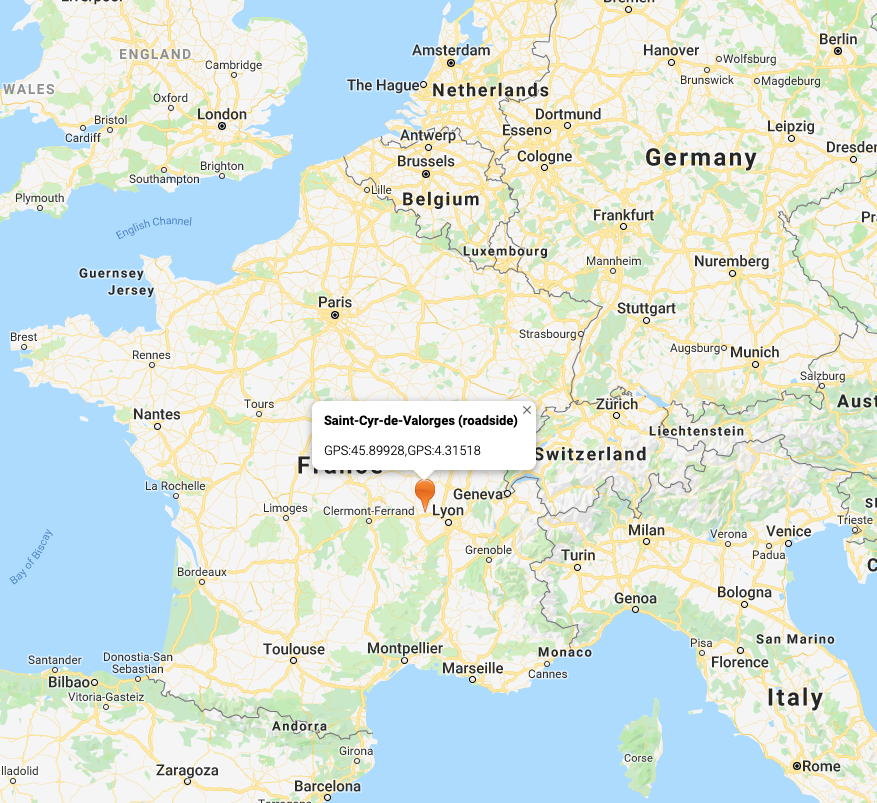

Chuckie and his fellow crew onboard B-24D serial no. 42-40997 The Worry Bird (formerly Screamin’ Mimi of the 565th Bomb Squadron, 389th Bomb Group) clipped a hill near its drop zone in Saint-Cyr-de-Valorges, Loire, and crashed killing him and four other crew; three airmen survived.

When it struck the ground on the third downward circle, the B-24 divided into four distinct compartments as it crash landed.

Chuckie and the four other airmen in the first to sections were killed; the three airmen in the back two sections survived after being able to parachute out and away from the plane to safety just before the crash landing.

- bombardier-navigator’s compartment in the nose of the aircraft which contained the navigational equipment, bomb-sight, bomb controls, and nose guns or nose turret; where navigator Lieut. Arthur B Pope, Navigator; and bombardier Lieut. Peter Roccia, Bombardier were located

- flight deck which included the pilot’s compartment, radio operator’s station, and top gun turret; where flight engineer Chuckie along with pilot Lieut. George W Ambrose and co-pilot Lieut. Robert H Redhair were located

- bomb bay compartment in the center of the aircraft under the center wing section (half deck is located above the rear bomb bay); where survivor Sgt. James C. Mooney was located

- rear fuselage compartment which contains the lower gun turret, waist guns, bottom camera hatch, photographic equipment, and the tail gun turret; where survivors Staff Sgt. James Heddleson and Sgt. George Henderson were located

Radio operator James Heddleson and gunners George Henderson and James C. Mooney survived. Heddelsman wrote a first person account of the crash in a letter to author Ben Parnell for his 1987 book Carpetbaggers: America’s Secret War in Europe. A transcription is in the archives at the Air Force Academy. A portion is reprinted here.

1st I hit my forehead, partly falling out and then I was thrown backwards toward the “Joe Hole” area, with the back of my head slamming into something in the plane. Sgt. Mooney is gone, he apparently fell out of the “Joe Hole.” I found out later he held onto the chutes (packages). Luckily he wasn’t killed, although the poor man must have suffered terribly. His back was broken, this I was told later. Sgt. Henderson was immediately out of the tail section.

We found each other.

Henderson and I were apparently fairly close to each other … as each of us made our way back to the plane.The plane seemed to be everywhere

Our plane could be seen like a beacon for miles like a beacon.. . . the ammunition exploding and whatever was in the canisters also going off. . . and the noise it made in the still of the night with everything exploding certainly would attract a lot of attention.The canisters were scattered everywhere.

The French worked very hard throughout the night, very hard, trying to retrieve them. Sgt. Henderson and I were apparently fairly close to each other and as each of us made our way back to the plane, we found each other.We assumed everyone was killed except Sgt. Mooney.

Mooney, we tried to find him, hoping he was alright, but it was night and in the mountain area and after a while we gave up. We were not only hurting physically, but also emotionally, myself being only 20 years old at the time.We could hear noises like cars or truck engines or so we thought.

Edited from transcribed copy of letter by crash survivor James Heddelson in the archives at the Air Force Academy June – 1998

My left leg was hurt and was getting worse as it was swelling around the knee. We had no idea where we were, but the 1st thing we thought of was it could be the Germans.

We started down the hills toward the valley,

Not knowing anything about the territory, we just decided to slip away in the night, the best way we could.

His back broken, Mooney was helped from the crash area by a French women from the village but was soon handed over to the Germans for urgent care when the seriousness of his injuries became clear. He survived as a POW in a Lyon hospital recovering from his injuries. Heddleson and Henderson successfully evaded the enemy by first hiding under cover, then being taken in by the French Resistance Army the Maquis, living with them for three months and even going along one night to help blow up a railway trestle. In early August an RAF Lockheed Hudson picked them up safely and on 27 August 1944 they returned to Harrington.

Coming up The Crash (Part four): What happened the next day when then sun came up and photos of the crashed plane.