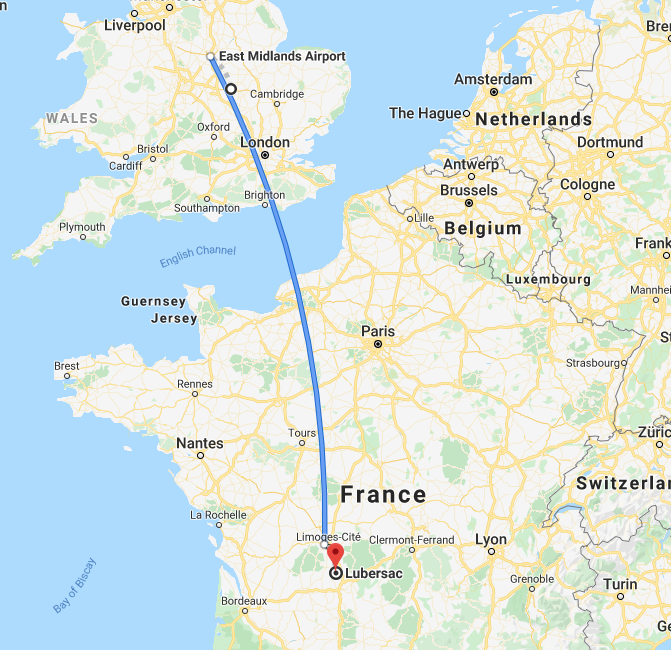

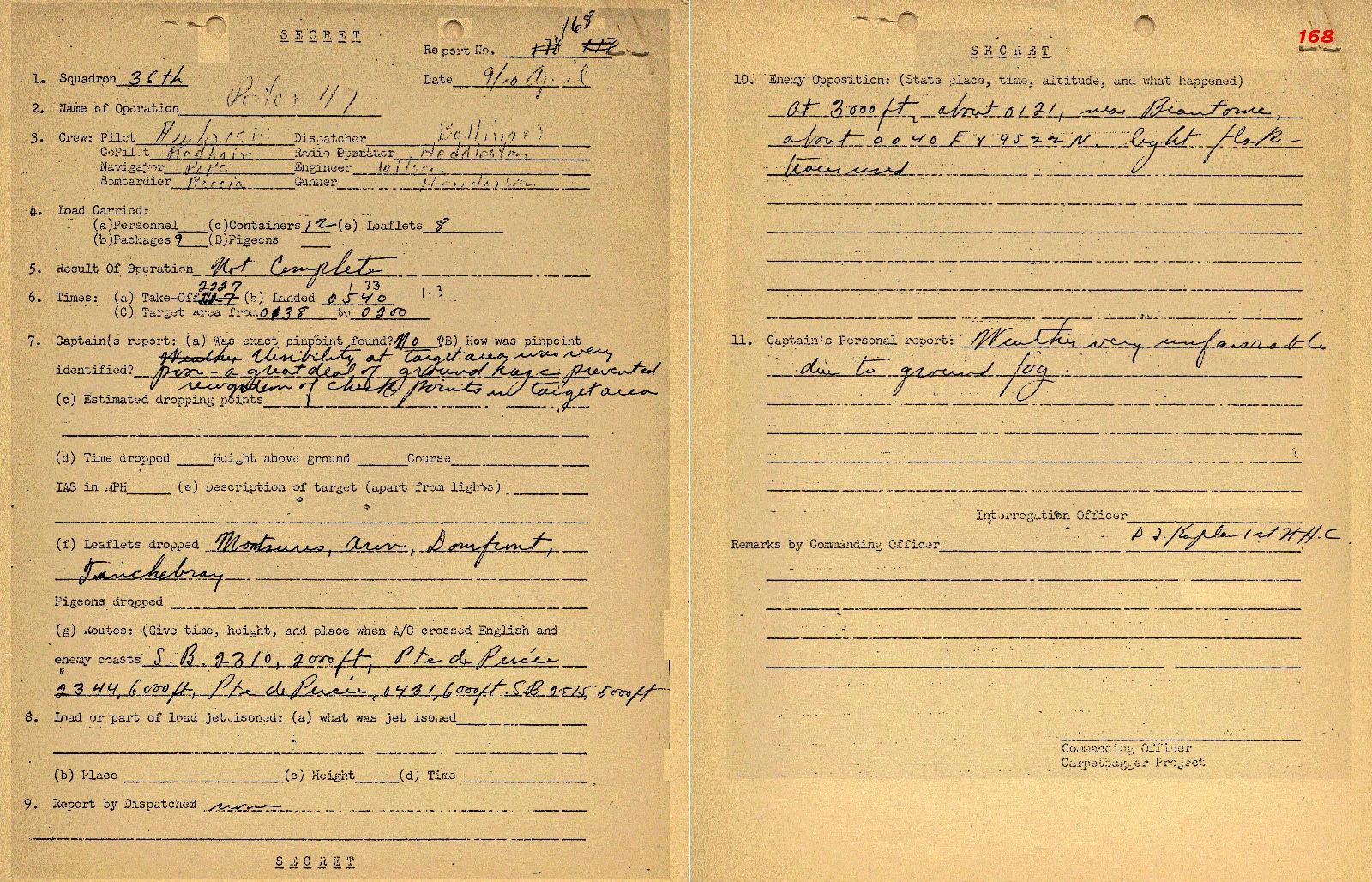

Operation “Lackey 3A” – Each Carpetbagger mission completed at Harrington took place in a 36 hour cycle, which began at 17:00 hours the day before the flight, when the OSS in London gave Lt. Robert Sullivan a list of approved targets for the following night. Based on historical documents and the Harrington Museum website, it is possible to frame out Chuckie’s schedule on his last day on earth before he took off with his crew into the dark night sky.

9AM – Weather report & targets

The Commanding Officer selected the night’s targets according to priority of requests from the Resistance groups, reception record of the group, and availability of crews and aircraft. The lists were then given to OSS, who informed the reception teams on times and recognition codes. The Station Weather Officer advised the Commanding Officer, or his deputy, of weather conditions anticipated in the target areas, and at it is decided where it will be practical to send Chuckie and The Worry Bird aircraft.

11AM – Target agreed

Chuckie’s Squadron Commander is called in and meets before a map in the Group Operations Room with the tabs pinpointing the targets for the night. Together, the squadron leaders select targets for their crews, balancing the difficult with the comparatively easy, the distant with the near, so that each squadron finally will have about the same work load.

Noon – Navigator receives targets

The navigators of the crews receive their targets from the Squadron Navigator. The Worry Bird crew navigator turns in a flight plan to his Squadron Navigator by 3PM. A take off time for Chuckie and his crew is agreed.

3PM – Loading the aircraft

Chuckie and his crew meet with an S-2 Officer and had the opportunity to study the S-2 map and to compare it with their own map. Crew maps are checked for location of the target (latitude, longitude and terrain features).

4:30 PM Chuckie attends final briefing

Chuckie attends a final briefing session with all crew members. The Intelligence Officer gives any special information which may affect the crew. Next, the Deputy Commander gives general flying and dropping instructions, and finally the Group Navigator gives instructions on the route to be followed whilst over England and the point and altitude for crossing the English coast. He ends up by giving the men a ‘time check’, on which all crew watches are synchronised.

06:00 PM Squadron Commanders and crew navigators briefed

All details, and weather to be expected en route to the drop zones were reviewed. The Worry Bird crew navigator briefs them on the course, the type of reception signal, the code recognition letters for the target, and the terrain features approaching and around the target.

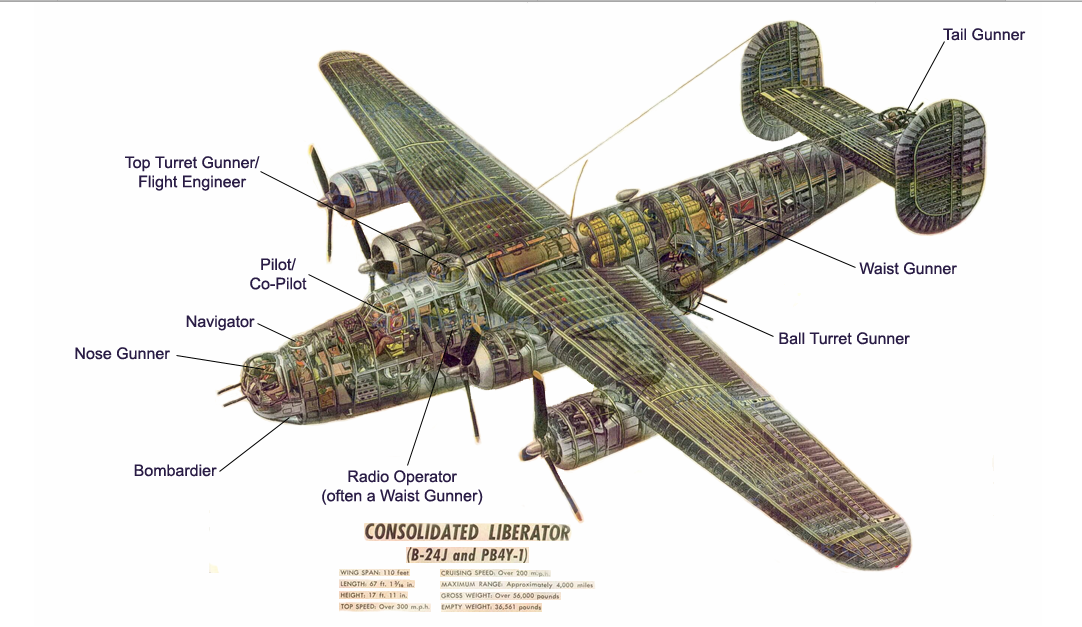

09:00 PM Pre-flight visual check

As the Engineer, Chuckie would have done a pre-flight visual check of the plane prior to take off, and make sure that the gas caps were secured. The Engineer was also responsible to see that the wheels were always locked (prior to landing), and some reports say there were times when he had to lower them by crank, from inside the plane.