The Ambrose Crew had better luck on its second operation.

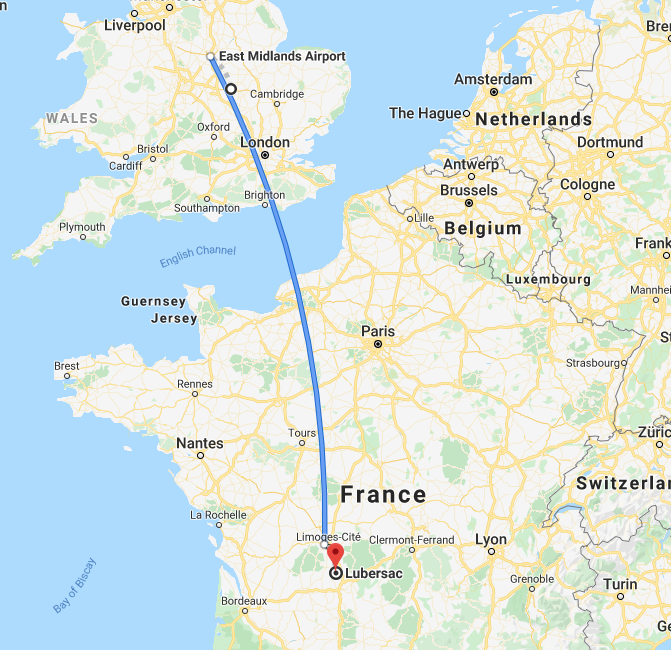

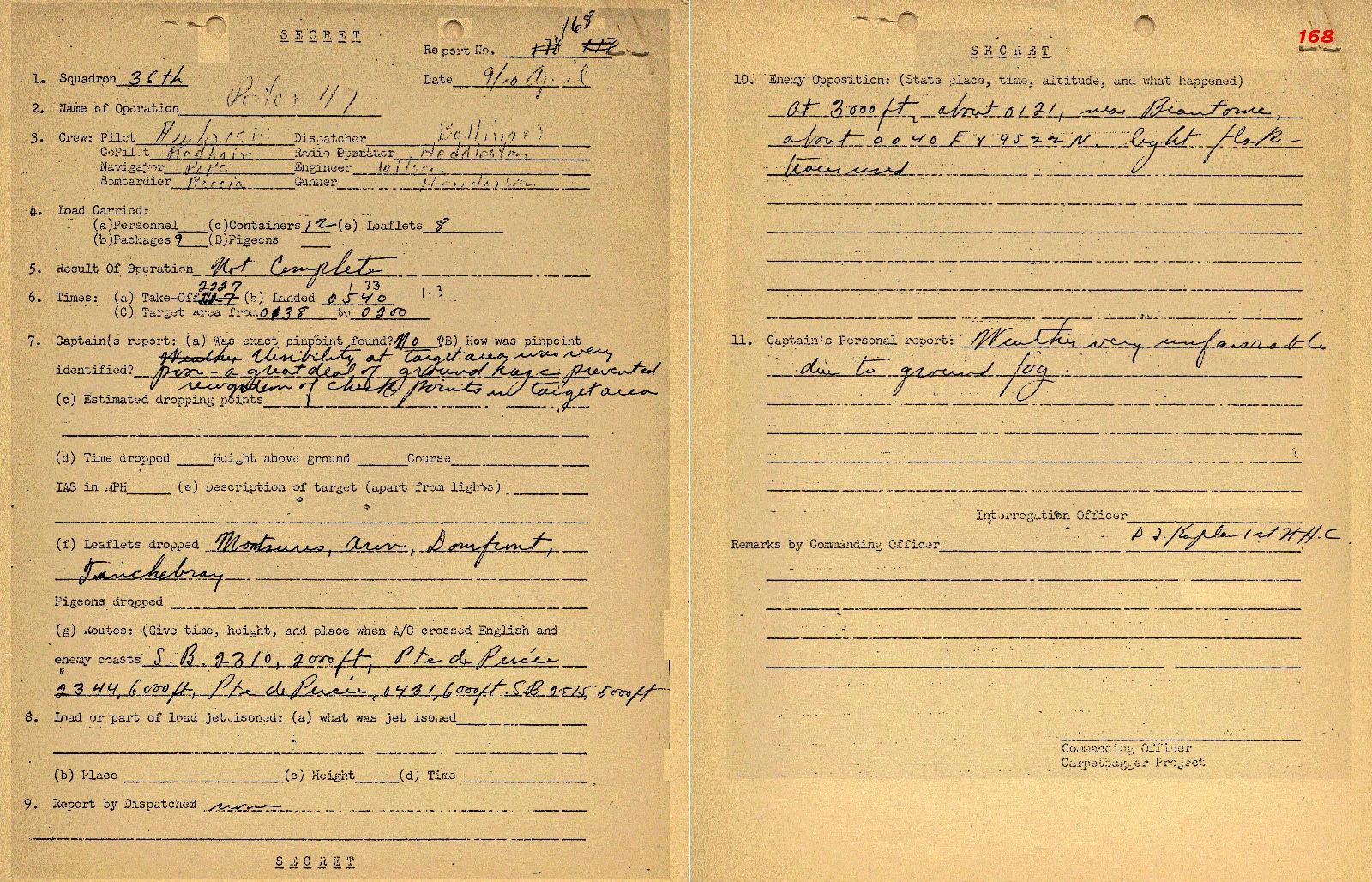

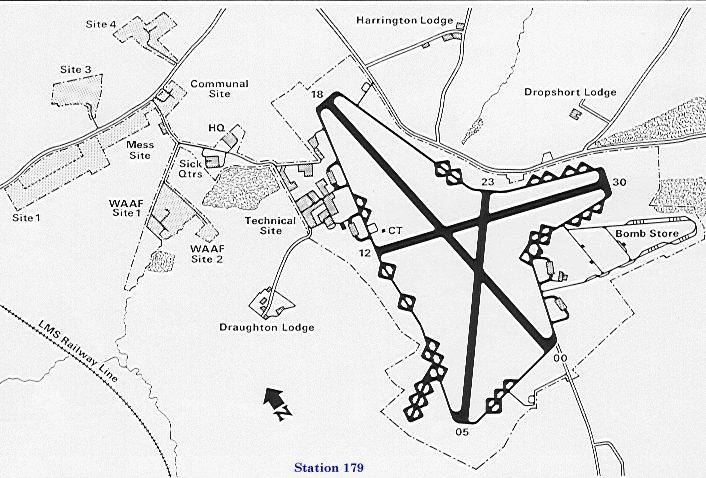

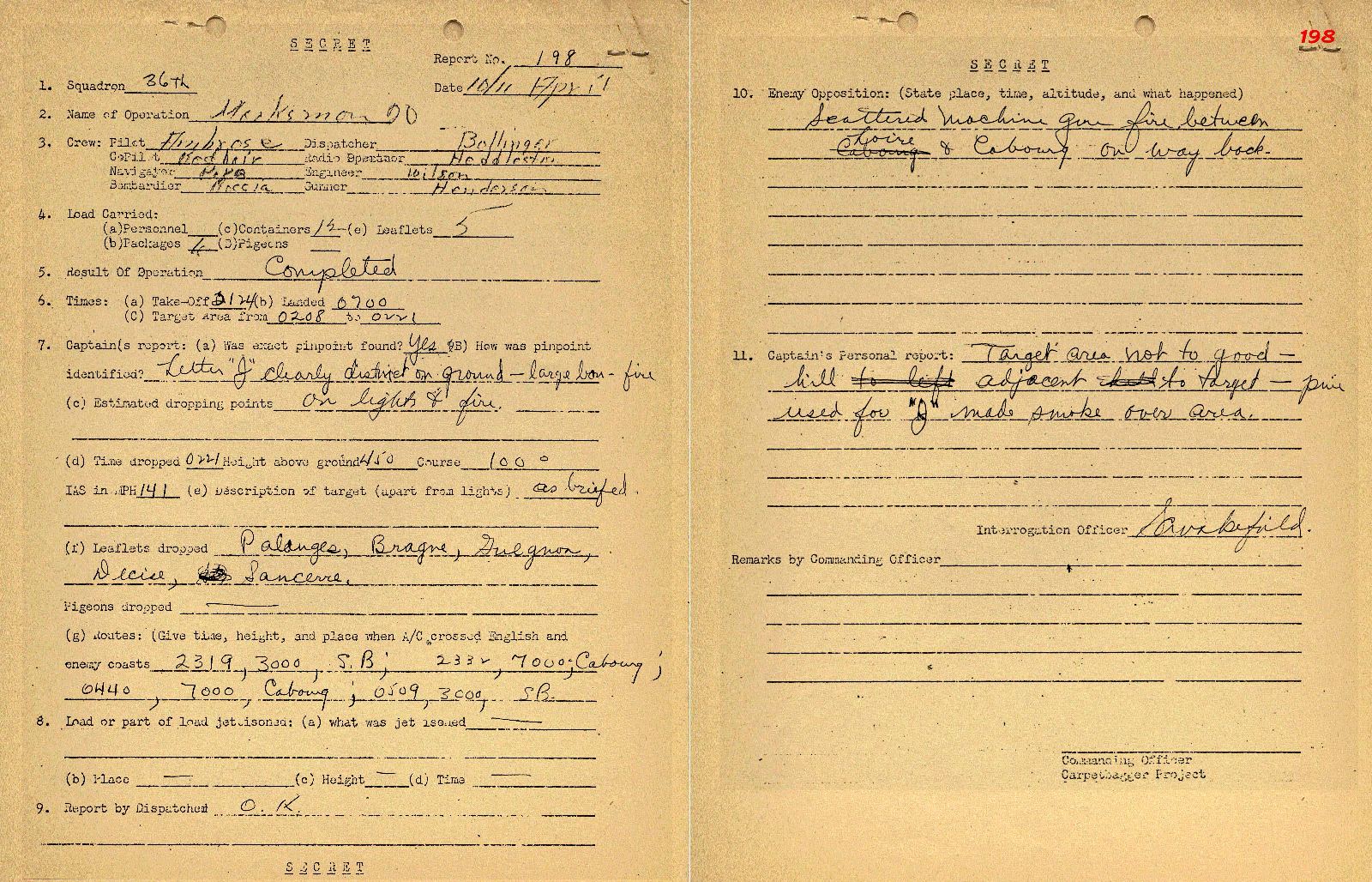

Report 198 notes the results of the nine and half hour operation “Marksman 20” as completed. After flying a few hours to behind enemy lines in France, Chuckie and his fellow crew dropped 12 containers, 6 six packages and 5 leaflets in France and returned safely back to Harrington in England.

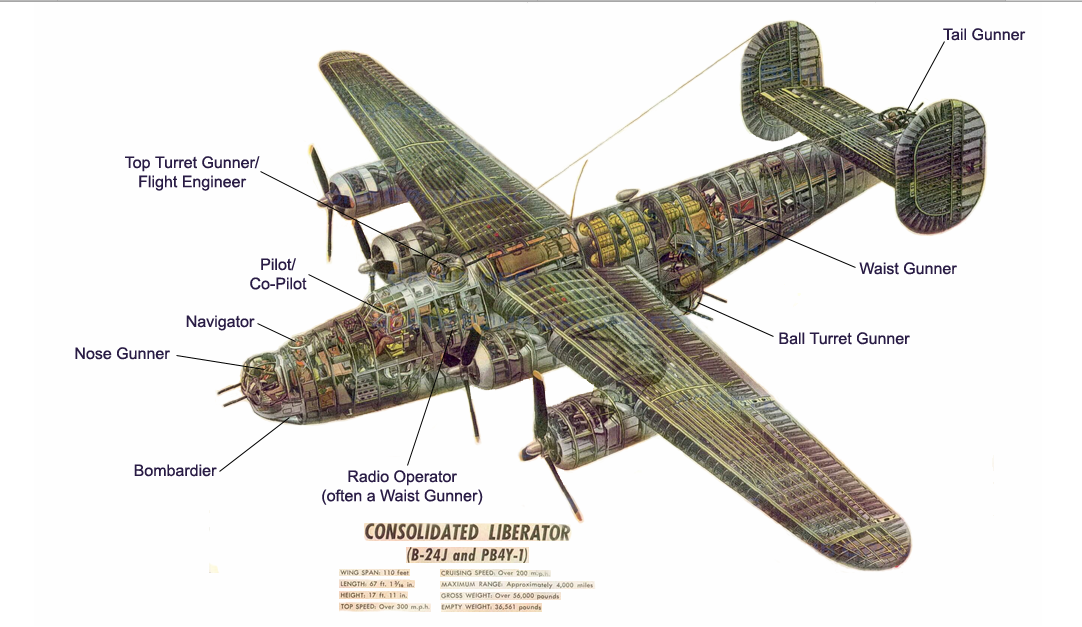

Loading the aircraft

Once the flight was confirmed, the target went to the OSS Liaison Officer at Harrington so that he could draw up a list of required containers and packages and arrange delivery to the plane. Containers were consigned to the Group Ordnance Officer, whose men first snapped on parachutes then delivered them to The Worry Bird where Armament Section men stood ready to load the containers into the aircraft. Packages are delivered to the Armament Officer and taken to the aircraft also for loading.

Leaflets were used to disseminate both pro-Allied and anti-Axis propaganda, with the aim of damaging enemy morale and sustaining the morale of the occupied countries. Usually six to ten bundles of 4,000 were loaded onto the plane according to the stock on hand, the length of flight and the time over enemy territory. No leaflets are dropped near Carpetbagger targets, for security reasons.

The OSS Liaison Officer and his men check each aircraft to ensure that the proper loading is in place.

The Worry Bird is ready for take off.

Report 198: Chuckie and his crew took off at 9:24PM in the evening and returned at 7AM the next morning. They found the pinpoint, the letter “J” was clearly distinct on the ground from a large bonfire. Flying just 400 feet above the ground, they made the drop of containers and packages to the resistance members.

After leaving the target thirty to fifty miles behind, the dispatcher drops the leaflets on villages and towns passed over on the homeward flight.

They encountered “scattered machine gun fire” between Loire, a river in West central France, and Cabourg in the Normandy region of France on the English channel.

Pilot Ambrose’s personal report: “The target area was not to (sic) good. Hill adjacent to target – pine used for J target made smoke over the area.” The intelligence gathered on the flights was valuable for improving operations and helping guide more successful future operations.

Chuckie must have been exhausted from the long mission but likely also exhilarated from the adrenaline, proud of his crew’s success that night.