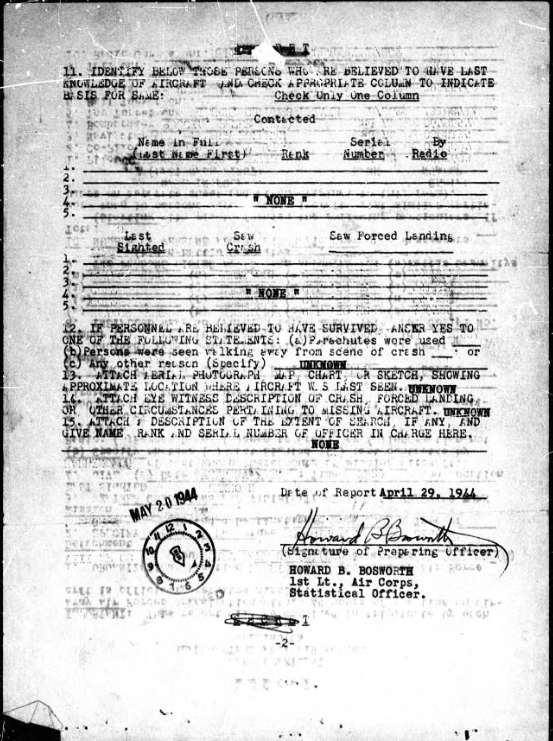

Two months after Chuckie’s parents first received news that he was missing in action, they received a second letter from the Government. This one from the United States Senate Finance Committee dated 21 June 1944 extending their sympathy. It contained no new information but now addressed as “my dear Mrs. Wilson.”

My dear Mrs. Wilson

I wish to extend to you my heartfelt sympathy because of the report that your son, Staff Sergeant Charles M. Wilson, has been reported as missing in action in the European Area.

If he has not been found or has not returned to his outfit by the time this letter reaches you, I sincerely hope that will occur in the very near future, and that when he does return he will be safe and sound.

With my kindest regards and best wishes, I am

Letter to Chuckie’s mother, dated 21 June 1944, from US Senate Finance Committee

Sincerely yours,

I was curious to know why the Senate Finance Committee would send such a letter so Googled it. The Finance Committee had the responsibility to raise revenue to pay for the buildup to WWII. They also had responsibility for funding and administering pension and benefits programs to veterans, widows and their children.

By 1941, Germany had conquered most of Europe and had begun its bombing campaign against Britain. And the Japanese had joined the Axis powers. Meanwhile, in the United States, the boom in the defense industry had helped bring the country out of the Great Depression.

The Finance Committee had the responsibility to raise revenue to pay for the buildup. The result was some of the largest revenue measures in the nation’s history, affecting all Americans. By early 1942, the Federal Government was spending $150 million a day, or roughly $5 billion a month, with nearly half of this total going towards the war effort.

The letter was signed by two individuals.

Senator Walter F. George (Georgia) Chairman of the United States Senate Committee on Finance

In the 1940s George supported President Roosevelt’s efforts at military preparedness and American defensive buildup in response to the threat posed. Once the United States entered World War II after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, George embraced the president’s vigorous prosecution of the war.

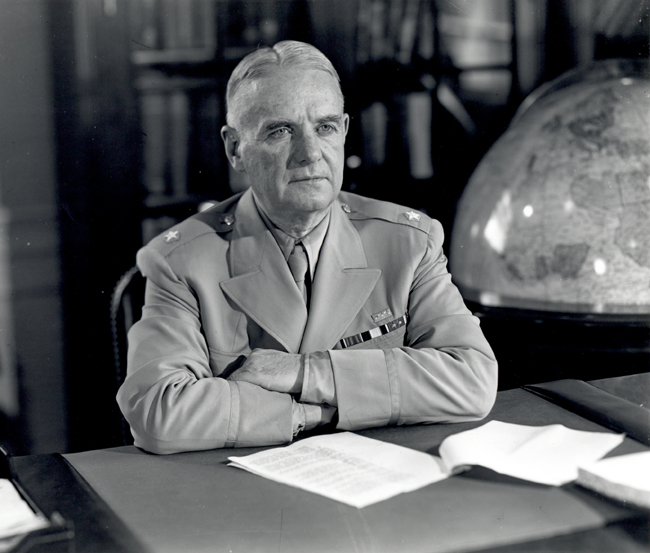

Major General Hugh J. Gaffey

At this time, he was chief of staff of the Third Army, serving again under Lieutenant General George Patton. Gaffey served in this capacity through the campaign in Western Europe, from the time the Third Army landed in France in July 1944 and played a major role in Operation Cobra and the Battle of the Falaise Gap, followed by the Allied advance from Paris to the Rhine and the Battle of Metz.