Part one of four posts capturing the story of what actually happened that night of the fiery crash that killed Chuckie compiled from two first person survivor accounts, historical documents filed in the Missing Aircraft Report and WWII archival material.

Chuckie’s Carpetbagger mission the night he was killed was Operation Lackey 3A over the Timdale drop zone detailed in an earlier post. When his aircraft reached a position a few miles from the drop zone near Lyon, France the ‘S’ Phone was used. The system permitted direct two-way voice communication with an aircraft up to a range of 30 miles and the agents on the ground working behind enemy lines to communicate and coordinate landings and the dropping of agents and supplies. It was composed of a “Ground” transceiver and an “Air” transceiver and required the ground operator to face the path of the aircraft. It had the useful trait of transmitting signals that could not be picked up by enemy ground monitoring stations more than one mile away.

“He called over the interphone that he spotted the target.”

It was around 1:00AM in the morning when Chuckie and crew reached the target area. According to the first person account from survivor Sgt James Heddelson, they made the 1st pass over the pinpoint and members of the Resistance on the farmland below for identification. While the S-Phone provided directional information to the pilot it gave no range information for the drop. This could only be done by visual sightings of lights on the ground.

A few miles from the target area all available eyes began searching for the drop area, which would usually be identified by three high powered flashlights placed in a row, with a fourth at a 90 degree angle to indicate the direction of the drop. The recognition torches were placed in the pre-arranged pattern and the light codes were exchanged between the ground and the plane. The aircraft was most vulnerable to enemy fire over the drop zone. The pilot 1st Liet. George Ambrose wasted no time lining up the twinkling markers.

“We circled around for position to make the drop.”

Pilot Ambrose selected half flaps and made the run in at 135 mph – not much above stalling speed. He was guided by the bombardier, who would be releasing the containers over the drop zone. Speed was all important on the ground – the man sized containers were to be quickly taken away into the cover of trees.

(2nd pass) . . . the wing flaps start to come down and the bomb bay doors are starting to open. Suddenly they start back up, we don’t drop and it is like we were practicing and we climb back up.”

“As we start to circle around again, I can still see the lights on the ground in the distance on our drop area. We start in for the 3rd pass.“

“Sgt James Mooney is over the “Joe Hole.” He volunteered for this mission (his first) we only met him shortly before take-off, as a regular crew member Sgt. W. Bollinger reported off sick. I am over the smaller hole behind Sgt. Geo. Henderson, who is in the tailgunners position, getting ready to throw some packages out. Once again the flaps start down and the bomb-doors open and we are starting our approach. I can look out and see the hills, or mountains on our left side.“

“Suddenly the plane shakes violently. Apparently we hit or clipped something.”

Coming Next: The Crash (Part Two) – The plane hits high ground

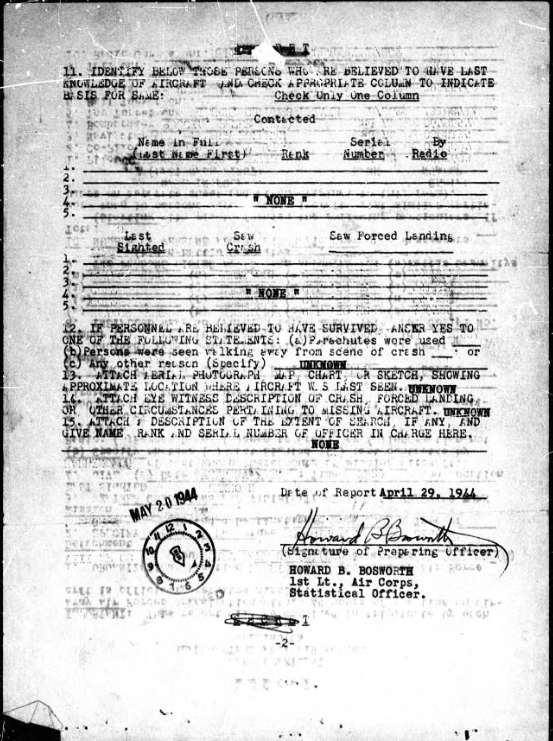

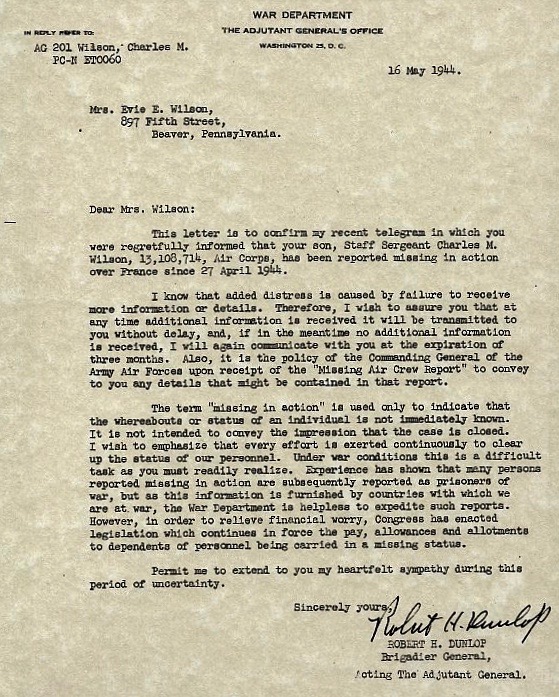

Credits: Edited quotes compiled from crash survivor Sgt. Geo. Henderson and Sgt. James Heddelson Interrogation Reports detailing when they last had contact with Chuckie; and a first-person account transcribed from copy of letter from crash survivor Sgt. James Heddelson in the archives at the Air Force Academy.