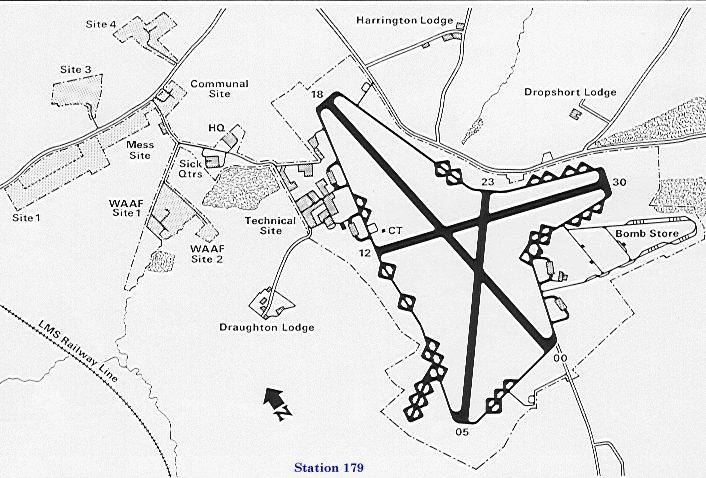

Chuckie’s 36th Bombardment Squadron moved into a more secluded, more secure airbase Royal Air Force Station (RAF) Harrington on 25 March 1944. It was built for heavy bomber use, the main runway length being about a mile. Approximately 860,000 square yards of concrete were laid, with one and three quarter million bricks being used, 210,000 cubic yards of soil being moved and 6 miles of roadway formed.

Chuckie was part of the initial operational squadron at Harrington. When they moved there, his 36th Bombardment Squadron was assigned to the 801st Bombardment Group.

US Army Engineers and local contractors.

The Group had already adopted the nickname of “Carpetbaggers” from its original operational codename. A Carpetbagger Aviation Museum at the site of the former airfield has on its website interesting photos and other historical information that provided me with additional details about the last weeks of Chuckie’s life.

It was loud, busy and always noisy, by all accounts. Yet looking at this 1944 B&W photo, even today, one can almost smell the fresh cut grass of the airfield and clearly see the beauty of a green English countryside that Chuckie and his crew would have experienced every day.

Afternoon lineup (photo taken looking south) at the airfield

where Chuckie’s plane took off from at RAF Harrington

Sadly, Chuckie was Killed in Action in the first month of Carpetbagger’s six months of operations at Harrington in 1944. Its operations peaked in June and July 1944 and on 13 August 1944, the Carpetbaggers at Harrington were re-designated as the 492nd Bomb Group (BG). Carpetbagger operations came to a practical end on the night of 16/17th September 1944.

The 492nd BG at Harrington continued supply dropping, bombing and missions until 7 May 1945 when Germany finally surrendered. They then left Harrington for Kirtland Field, Albuquerque, New Mexico where they later joined up with the ground echelon who had travelled back to America by the ocean liner Queen Elizabeth. The Group deactivated on the 17th October 1945.

Following the withdrawal of the Americans, Harrington airfield fell into a period of disuse and returned to farmland. It received a new lease of life when it was selected to become one of the RAF’s Thor missile sites in the late 1950’s. The site was again abandoned in 1965 and the buildings, runways and most of the roads and taxiways were demolished.

Today, the foundations of some WWII buildings can still be seen around the site of the airfield, the only remaining original substantial WWII buildings left standing are where The Carpetbagger Aviation Museum is now housed in part of the original Operations Building at the airfield’s administration site.

I hope to get there one day to take in the English countryside view Chuckie saw the last day he saw daylight – 27 April 1944.